Indie Filmmakers

Why They Need to Work on Their Storytelling Skills

By Jeffrey Winters

When I used to live in San Francisco I wrote film reviews for local papers, went to film school, pitched a love story in Hollywood and made a small film. Then in 2004 I moved to the beautiful alpine mountain town of Mount Shasta, where I founded and directed The Mount Shasta International Film Festival from 2004–2009. (www.shastafilmfest.com)

Filmmakers submitted hundreds of shorts, documentaries, foreign feature films and American Indie features to the selection from which we programmed the films that would be shown in the festival. We began to see a pattern with the American indie features which was unfortunate. Many of the directors had technical skills that were impressive, but many didn’t know the basic rules of Storytelling.

Storytelling has firm rules and a dramatic structure, which applies to mythology, love stories, drama, indie features, thrillers, character-driven and plot-driven films, and even comic books. The festival received so many indie features in which the basic rules of storytelling were either unknown to the filmmaker, or ignored, and the storytelling never synched with their technical virtuosity, which often was quite impressive.

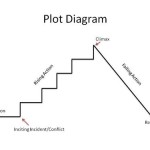

The basic template for storytelling uses a three-act structure. This was established a long time ago, and can be observed in the plays of the ancient Greeks. The structure includes exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution. It’s simple and satisfies the emotional needs of most audiences.

Exposition defines the conflict and offers a glimpse into the characters. What most early career filmmakers often fail to do is to hook the audience in the first ten minutes, with some form of caring, curiosity, dislike or empathy towards the main characters. At the same exposition is used to define the conflict and obstacles the main character must overcome. It is, in many ways, the start of a journey.

Be it indie or commercial film, the most difficult film to make successfully is comedy. Larry Tucker, the writer of the 1969 comedy Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice.

Be it indie or commercial film, the most difficult film to make successfully is comedy. Larry Tucker, the writer of the 1969 comedy Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice.

“A love story is never about watching them in love together. It’s always about what it takes for them to get together.” The late great Nora Ephron wrote two films that delighted audiences worldwide and showed this principle: “You’ve Got Mail,” and “Sleepless In Seattle.” Both films demonstrate the power of exposition, the conflict between the main characters, the journey to love take place and the resolution.

The rising action (Act Two) is the most difficult part of the film for many indie filmmakers to write and edit. That’s because the middle is always difficult to define. Act Two shows how the characters live, breath, love, eat and overcome adversity. If it is a plot driven film you go from scene to scene. If it is a character study, you unveil the shadow side of the character and how it relates to his or her persona. The middle of the film shows the activity, struggles, attempts, humor, hardship and humanity of our characters. It’s the part of a journey where other lesser important characters must integrate into the film. It is the place where the writer and director’s understand and skill showing human nature is required. Sometimes the wrong choices are made, and the audience loses the thread of the main story or the arc of the main characters’ journey. This is often due to poor editing, too many distractions, and not using the secondary characters to support and clarify the dramatic arc of the main characters.

The climax (Act Three) of the film is brief. The climax is the turning point, which marks a change, for the better or the worse, in the protagonist’s affairs. Either the man gets the girl and they kiss, or the person overcomes the obstacle and we see that, but little time is spent showing it. The end of a good story can leave you sad, mad, happy or confused. The good guy proves he is innocent. The family finds or loses their kidnapped child. Tom Hanks gets Meg Ryan. The abused person confronts the priest.

What follows is called Falling Action. During this phase of the film, the conflict between the protagonist and the antagonist unravels, with the protagonist winning or losing against the antagonist. The falling action may contain a moment of final suspense, in which the final outcome of the conflict is in doubt.

Finally we are at the end of the journey, and now we need to give the audience a little something to reflect upon and carry home with them. It’s called the resolution. It’s often a restatement or confirmation of what they have already seen. It could be in the form of a speech by one of the characters, as often seen in Shakespeare. This could take the form of a quick wrap up of how they overcame the obstacle or didn’t overcome and succeed. As the audience leaves the theater or after they watch the film on TV or video, something remains with them. Something important. That something is the “message” of the film, the concept or idea, which is the central theme of the film and an issue of importance to the characters and the filmmakers.

I’ve seen many indie films where the filmmaker thought it was hip to leave the ending out, then “explain” us at the Q&A, “I wanted to audience to figure it out and make their own conclusions.” Sorry, but some filmmakers just don’t get it. It’s not the audience’s job to tell the story, it’s the job of the filmmaker. Sure, there can be endings that leave some things unresolved, but the main theme of the film must be made clear, or it’s like painting most of a room, and then leaving a corner unpainted. For some with telepathy who can figure out what the director had in mind, that might work. But audiences usually feel ripped off by poor storytelling. It is the filmmaker’s job to tell a good story, to respect the audience’s intelligence, and to satisfy the audience’s emotional needs. If you ever wonder why some films are classics and stand the test of time, this is why!

I think the remedy is simple. Study storytelling. Watch both independent and commercial films that succeed because the story is well told. Read mythology. Learn the template of exposition, rising action, climax and resolution. It’s the way we dream and why it works so well. It’s also like sex (think about that for a minute). Ah, now you understand!